Guide

Learning more about birds.

Now that I’m more involved with birding and birds photography, let me tell you that it’s not easy to identify a bird with certainty. Every little detail counts in order to get the right description of any specie. Elements of size, color, shape, habitat, location, etc. The list is long and it takes caution and patience before you can jump to a conclusion.

From what I’ve been learning and researching I’ll try to pass a little bit of these tips in case that you might need a guide.

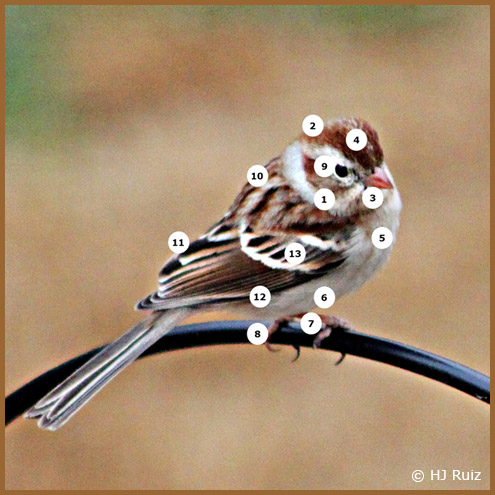

Let’s start with learning a bit of the bird parts, what are they called?

- Moustachial stripe

- Lateral crown-stripe

- Throat

- Crown-stripe

- Breast

- Belly

- Tarsus

- Toe

- Eye ring

- Mantle

- Rump

- Flank

- Greater-coverts

These are some of the names of different parts of the bird’s body.

This topic of Bird Anatomy is very interesting and will be uploaded in several parts then the articles will be added to GUIDE section (See top bar of blog)

Bird anatomy, or the physiological structure of birds’ bodies, shows many unique adaptations, mostly aiding flight. Birds have a light skeletal system and light but powerful musculature which, along with circulatory and respiratory systems capable of very high metabolic rates and oxygen supply, permit the bird to fly. The development of a beak has led to evolution of a specially adapted digestive system. These anatomical specializations have earned birds their own class in the vertebrate phylum.

Let’s start with:

PART 1

RESPIRATORY SYSTEM

Due to their high metabolic rate required for flight, birds have a high oxygen demand. Development of an efficient respiratory system enabled the evolution of flight in birds. Birds ventilate their lungs by means of air sacs.

These sacs do not play a direct role in gas exchange, but to store air and act like bellows, allowing the lungs to maintain a fixed volume with fresh air constantly flowing through them.

Three distinct sets of organs perform respiration—the anterior air sacs (interclavicular, cervicals, and anterior thoracics), the lungs, and the posterior air sacs (posterior thoracics and abdominals). The posterior and anterior air sacs, typically nine, expand during inhalation. Air enters the bird via the trachea. Half of the inhaled air enters the posterior air sacs, the other half passes through the lungs and into the anterior air sacs. Air from the anterior air sacs empties directly into the trachea and out the bird’s mouth or nares. The posterior air sacs empty their air into the lungs. Air passing through the lungs as the bird exhales is expelled via the trachea. Some taxonomic groups (Passeriformes) possess 7 air sacs, as the clavicular air sacs may interconnect or be fused with the cranial thoracic air sacs. Birds lungs obtain fresh air during both exhalation and inhalation.

As air flows through the air sac system and lungs, there is no mixing of oxygen-rich air and oxygen-poor, carbon dioxide-rich, air as in mammalian lungs. Thus, the partial pressure of oxygen in a bird’s lungs is the same as the environment, and so birds have more efficient gas-exchange of both oxygen and carbon dioxide than do mammals. In addition, air passes through the lungs in both exhalation and inspiration, with the air sacs functioning as a reservoir for the next breath of air.

Avian lungs do not have alveoli, as mammalian lungs do, but instead contain millions of tiny passages known as parabronchi, connected at either ends by the dorsobronchi and ventrobronchi. Air flows through the honeycombed walls of the parabronchi into air vesicles, called atria, which project radially from the parabronchi. These atria give rise to air capillaries, where oxygen and carbon dioxide are traded with cross-flowing blood capillaries by diffusion.

Birds also lack a diaphragm. The entire body cavity acts as a bellows to move air through the lungs. The active phase of respiration in birds is exhalation, requiring muscular contraction.

The syrinx is the sound-producing vocal organ of birds, located at the base of a bird’s trachea. As with the mammalian larynx, sound is produced by the vibration of air flowing through the organ. The syrinx enables some species of birds to produce extremely complex vocalizations, even mimicking human speech. In some songbirds, the syrinx can produce more than one sound at a time.

PART 2

Skeleton

The bird skeleton is highly adapted for flight. It is extremely lightweight but strong enough to withstand the stresses of taking off, flying, and landing. One key adaptation is the fusing of bones into single ossifications, such as the pygostyle. Because of this, birds usually have a smaller number of bones than other terrestrial vertebrates. Birds also lack teeth or even a true jaw, instead having evolved a beak, which is far more lightweight. The beaks of many baby birds have a projection called an egg tooth, which facilitates their exit from the amniotic egg.

Birds have many bones that are hollow (pneumatized) with criss-crossing struts or trusses for structural strength. The number of hollow bones varies among species, though large gliding and soaring birds tend to have the most. Respiratory air sacs often form air pockets within the semi-hollow bones of the bird’s skeleton. Some flightless birds like penguins and ostriches have only solid bones, further evidencing the link between flight and the adaptation of hollow bones.

Birds also have more cervical (neck) vertebrae than many other animals; most have a highly flexible neck consisting of 13-25 vertebrae. Birds are the only vertebrate animals to have a fused collarbone (the furcula or wishbone) or a keeled sternum or breastbone. The keel of the sternum serves as an attachment site for the muscles used for flight, or similarly for swimming in penguins. Again, flightless birds, such as ostriches, which do not have highly developed pectoral muscles, lack a pronounced keel on the sternum. It is noted that swimming birds have a wide sternum, while walking birds had a long or high sternum while flying birds have the width and height nearly equal.

Birds have uncinate processes on the ribs. These are hooked extensions of bone which help to strengthen the rib cage by overlapping with the rib behind them. This feature is also found in the tuatara Sphenodon. They also have a greatly elongate tetradiate pelvis as in some reptiles. The hindlimb has an intra-tarsal joint found also in some reptiles. There is extensive fusion of the trunk vertebrae as well as fusion with the pectoral girdle. They have a diapsid skull as in reptiles with a pre-lachrymal fossa (present in some reptiles). The skull has a single occipital condyle.

The skull consists of five major bones: the frontal (top of head), parietal (back of head), premaxillary and nasal (top beak), and the mandible (bottom beak). The skull of a normal bird usually weighs about 1% of the birds total body weight.

The vertebral column consists of vertebrae, and is divided into three sections: cervical (11-25) (neck), Synsacrum (fused vertebrae of the back, also fused to the hips (pelvis)), and pygostyle (tail).

The chest consists of the furcula (wishbone) and coracoid (collar bone), which two bones, together with the scapula (see below), form the pectoral girdle. The side of the chest is formed by the ribs, which meet at the sternum (mid-line of the chest).

The shoulder consists of the scapula (shoulder blade), coracoid (see The Chest), and humerus (upper arm). The humerus joins the radius and ulna (forearm) to form the elbow. The carpus and metacarpus form the “wrist” and “hand” of the bird, and the digits (fingers) are fused together. The bones in the wing are extremely light so that the bird can fly more easily.

The hips consist of the pelvis which includes three major bones: Illium (top of the hip), Ischium (sides of hip), and Pubis (front of the hip). These are fused into one (the innominate bone). Innominate bones are evolutionary significant in that they allow birds to lay eggs. They meet at the acetabulum (the hip socket) and articulate with the femur, which is the first bone of the hind limb.

The upper leg consists of the femur. At the knee-joint, the femur connects to the tibia-tarsus (shin) and fibula (side of lower leg). The tarsus-metatarsus forms the upper part of the foot, digits make up the toes. The leg bones of birds are the heaviest, contributing to a low center of gravity. This aids in flight. A bird’s skeleton comprises only about 5% of its total body weight. Birds feet are classified as anisodactyl, zygodactyl, pterodactyl, syndactyl or pamprodactyl.

1. Skull

2. Cervical vertebrae

3. Furcula

4. Coracoid

5. Uncinate processes of ribs

6. Keel

7. Patella

8. Tarsus-metatarsus

9. Digits

10. Tibia

11. Fibula

12. Femur

13. Ischium

14. Pubis

15. Illium

16. Caudal vertebrae

17. Pygostyle

18. Synsacrum

19. Scapula

20. Lumbar vertebrae

21. Humerus

22. Ulna

23. Radius

24. Carpus

25. Metacarpus

26. Digits

27. Alula

Photograph © H.J. Ruiz – Avian 101

Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License; additional terms may apply. See Terms of use for details.

SCIENTIFIC CLASSIFICATION – Example: SONG SPARROW

| The Song Sparrow (Melospiza melodia) is a medium-sized American sparrow. Among the native sparrows in North America, it is easily one of the most abundant, variable and adaptable species.This bird will be our subject for this explanation about Scientific Classification. |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | 1- Animalia |

| Phylum: | 2- Chordata |

| Class: | 3- Aves |

| Order: | 4- Passeriformes |

| Family: | 5- Emberizidae |

| Genus: | 6- Melospiza |

| Species: | M. melodia |

Each one of the classifications is explained in more detail below

1- Animals are a major group of multicellular, eukaryotic organisms of the kingdom Animalia or Metazoa. Their body plan eventually becomes fixed as they develop, although some undergo a process of metamorphosis later on in their life. Most animals are motile, meaning they can move spontaneously and independently. All animals are also heterotrophs, meaning they must ingest other organisms or their products for sustenance.

2- The Chordates are animals that comprise the phylum Chordata. Taxonomically the phylum Chordata includes three subphyla: Tunicata; Cephalochordata, comprising the lancelets; and the Craniata, or Vertebrata. The common attributes of the Chordata include having, for at least some period of their life cycles, a notochord, a hollow dorsal nerve cord, pharyngeal slits, an endostyle, and a post-anal tail. The phylum Hemichordata has been presented as a fourth chordate subphylum, but it now is usually treated as a separate phylum.

3- Birds (class Aves) are feathered, winged, bipedal, endothermic (warm-blooded), egg-laying, vertebrate animals. With around 10,000 living species, they are the most speciose class of tetrapod vertebrates. All present species belong to the subclass Neornithes, and inhabit ecosystems across the globe, from the Arctic to the Antarctic. Extant birds range in size from the 5 cm (2 in) Bee Hummingbird to the 2.75 m (9 ft) Ostrich. The fossil record indicates that birds emerged within theropod dinosaurs during the Jurassic period, around 160 million years (Ma) ago. Paleontologists regard birds as the only clade of dinosaurs to have survived the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event 65.5 Ma ago.

4- A passerine is a bird of the order Passeriformes, which includes more than half of all bird species. Sometimes known as perching birds or, less accurately, as songbirds, the passerines form one of the most diverse terrestrial vertebrate orders: with over 5,000 identified species, it has roughly twice as many species as the largest of the mammal orders, the Rodentia. It contains over 110 families, the second most of any order of vertebrates (after the Perciformes).

The names “passerines” and “Passeriformes” are derived from Passer domesticus, the scientific name of the eponymous species—the House Sparrow—and ultimately from the Latin term passer for Passer sparrows and similar small birds.

5- The Emberizidae are a large family of passerine birds. They are seed-eating birds with a distinctively shaped bill.

In Europe, most species are called buntings. In North America, most of the species in this family are known as (American) sparrows, but these birds are not closely related to the (Old World) sparrows, the family Passeridae. The family also includes the North American birds known as juncos and towhees.

The Emberizidae family probably originated in South America and spread first into North America before crossing into eastern Asia and continuing to move west. This explains the comparative paucity of emberizid species in Europe and Africa when compared to the Americas.

As with several other passerine families the taxonomic treatment of this family’s members is currently in a state of flux. Many genera in South and Central America are in fact more closely related to several different tanager clades, and at least one tanager genus (Chlorospingus) may belong here in the Emberizidae.

6- Melospiza is a genus of passerine birds in family Emberizidae. The genus, commonly referred to as “song sparrows,” contains currently three species, all of which are native to North America.

Members of Melospiza are medium-sized sparrows with long tails, which are pumped in flight and held moderately high on perching. They are not seen in flocks, but as a few individuals or solitary. They prefer brushy habitats, often near water.

I sure hope that some of this information will clarify some of the questions that you might have wondered when you read about birds.

More Useful Information

The sole purpose of this page is provide what we believe is very useful information related to Nature and Environment. All the necessary systems created to protect our loved Country’s wildlife and rich natural assets.

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Services

National Wildlife Refuge System

Georgia Department of Natural Resources

Very interesting and informative, thank you for this.

You are very welcome Marianne, I should be thanking you!

Informative website, thanks!

🙂

are you by any chance a teacher :). ‘Cause I feel like I just learned somthing

We all become teachers the moment that we have a child! If you’re referring to if I am an Ornithology teacher, the answer is no. I study on my own all about birds, there are many books I research plus the Web.

I’m glad that have learned something about birds. Thank you for your visit.

How did I miss this?? Thanks for sharing!

Thank you for visiting! By the way, tomorrow I’ll be posting something very interesting about birds. Don’t miss that! 🙂

Great!! Looking foward to it!

Glad I found you!

Yes, you did! 🙂

Very good informative, but guess what I always have a hard time identifying birds 🙂 especially sparrows.

Thank you guys for sharing! Good traveling! 🙂

Char posted an image of an unidentified bird in October 2017. She asked if any of her readers could ID the bird. After 18 months she still doesn’t know. H.J., can you solve this mystery at long last?

I have sent an email with the answer to Charity and the explanation to the conclusion. Thanks for helping, David. 🙂

Wow 🙂 at 65 and luv birds this was more info then I can absorb Thank-You for your knowledge and sharing with us 🙂

Never is too late to learn a bit more. 🙂